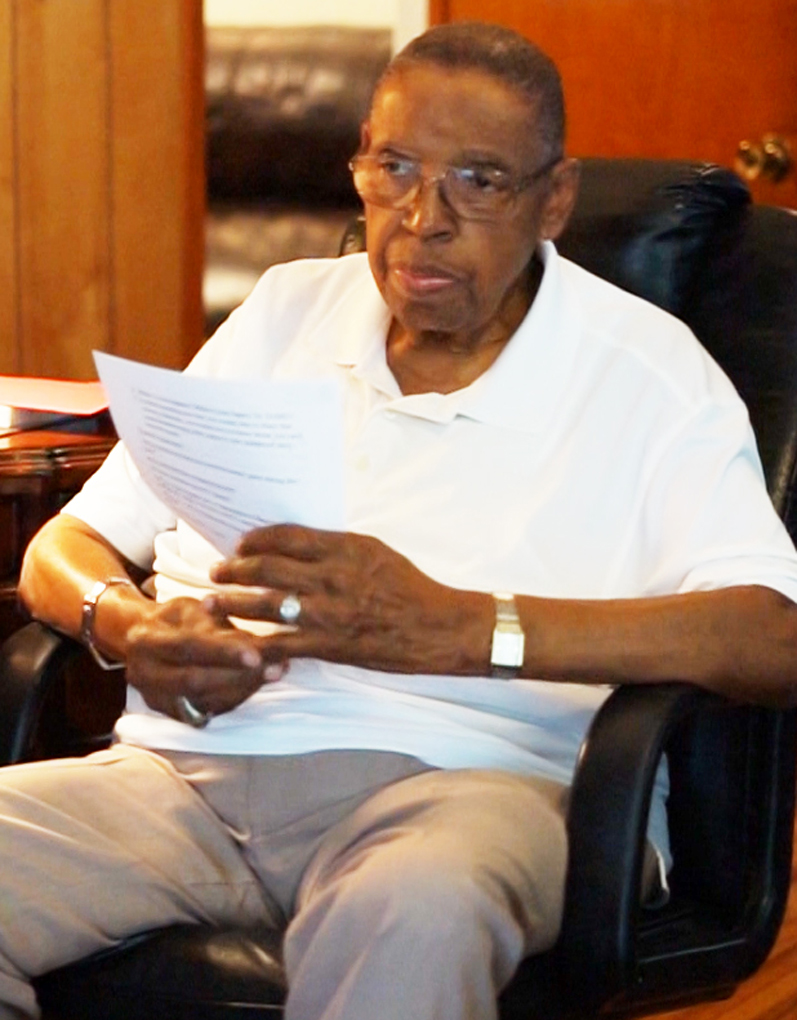

Birmingham Native Brought Jazz to The Hill

Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame Inductee

Birmingham educator helps usher in jazz on A&M campus in the late 1940s

by Jerome Saintjones

(from Interview conducted by Dr. Annie Payton,

J.F. Drake Memorial Learning Resources Center,

Alabama A&M University)

Noted Birmingham area educator and administrator Tolton Rosser was born in Birmingham, Ala., around the Depression. He recalled that during those days Pre-K was not established, so his mother hired a woman to look after him while she worked. The woman his mom had hired was also employed with a local school, and she would take young Tolton with her to Washington School from time to time. This occurred often enough that before he even knew what was happening, he was enrolled at the school as a first grader. Washington School enrolled students in grades 1-8 and was fairly close to his residence at the time.

Rosser completed all eight grades at Washington. But upon completion, because of where he lived, he had to transfer to Ullman High School, which he attended for two years, before it was closed by the racial integration effort of the 1960s. Those school grounds and memories are now covered by the growth of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), which bought the property in 1970. Following his first years at Ullman, Rosser enrolled at A.H. Parker High School for his last two years.

Prior to the high school years, however, Rosser considers himself fortunate in that, at a local church, there was a man who had been involved in band music in the military and who brought that expertise with him and urged several young men to play instruments. Rosser was among them. This man’s only payment was an understanding among the young men that they would form that church’s “unofficial” band. The man also understood that when his burgeoning young talent became old enough and good enough to join a high school marching band and wear those attractive uniforms, it would leave his tutelage and continue onward.

At Ullman High, he was further influenced by jazz musician Wilson Driver and a faculty member Rosser simply remembers as “Shakey,” who prepared the Ullman band for its later merging into the program at Parker High.

When Rosser first entered the halls of Parker, he had not even heard of Alabama A&M. At the time, Alabama State was “the” school in the area, he recalled, and prospective college-bound students tended to make the trip south toward Montgomery. A&M came to the forefront, however—at least for several at Parker High School—when it offered 30-35 band scholarships to band members, pulling a large group of them in an almost saintly endeavor northward and upward toward Huntsville.

In that march, Rosser was not in that number.

He had decided instead to connect to Birmingham’s vibrant music scene and to go on the road, playing with various traveling bands, including Gatemouth Moore. A general manager later convinced him that such a life wasn’t for him. A product of a broken home, there he was left to his own devices, in a city that offered him no magic. Yet, somehow, the band director at A&M at the time (Wilson) had heard that the talented Rosser had been left “stranded” in Birmingham and reach out to him.

When he finally made it to the gates of the A&M campus, the football season was well underway. Nonetheless, he was able to find his groove with the band and was quickly welcomed and brought up to speed by his former bandmates from Parker. He also met a few young men who were from Huntsville and had their own jazz combos that were performing around town. He was very interested and, since there was nothing remotely similar on campus at the time, Rosser joined the budding group of musicians and vocalist from A&M.

He then worked to pull together about five musicians from Birmingham and a few from Huntsville and, using what Rosser had learned about arranging and scoring in high school, the group soon found itself not only playing for basketball games, but receiving extra compensation in scholarship funding for their added efforts that went beyond the basic requirements.

“I was fortunate enough to have the fellows stick with me, to play the tunes we wrote, and to do a pretty good job,” said Rosser. “We started calling ourselves the A&M Collegiates. We were never formally named that. Although we were never given that title, everybody knew who we were, what we were doing and how we were doing.”

Rosser said that in those days, the library was literally “the end of the campus” for young men. The men could not venture into the Promised Land of the female territory beyond it. Rosser and company would stand on those limits and hum and sing. Not only would the young women come to the edge of their own campus-imposed limits, but the ladies would offer the musicians songs and ideas for their repertoire.

“We were able then to start putting together some sounds that made a lot of sense,” noted Rosser. “We started playing jobs on campus. All of the fraternities and sororities usually had parties of some kind, usually in the lunchroom—we didn’t have all the buildings and things that you have now. They would, in a sense, hire us.”

He explained that no one really had any money, but the student organizations would collect monies for the band. Some events might raise about $25 or more, he said. That amount split among four or five guys was “good money” for young men who were mostly isolated on the campus during those days of segregation, he said.

Rosser said the jazz combo began playing at what became Redstone Arsenal and some events throughout Huntsville. Rosser added that he definitely would have pursued studies in music at A&M, had a degree been offered at the time. His alternative was English and social studies, which enabled him to excel academically while still “doing his thing.”

The ad hoc jazz band continued to play on, and the members really enjoyed what they were doing, at least to the extent that they were able to matriculate together. Although he has the names of the fellows who took part in forming A&M’s intro into jazz, he sadly mutters, “They are all gone now; all of them are dead.”

The Powers That Be at A&M were not particularly interested in jazz, recalled Rosser. But fortunately, the band director and staff did not take issue with students performing the genre on their own, and that is where Rosser entered the picture and history was made through the forming of The Collegiates.

Even at 87, Rosser still regrets that he did not receive a degree in music. Yet, music has been good to Rosser, and it brightened the path he did take when it comes to his career. His professional life includes dedicated service as a band director, assistant principal, and principal for 30 years, until his retirement.

Throughout the decades, he was leading a dual life as a consummate musician and was still writing, arranging and scoring. Even today he directs the Birmingham Heritage Band. He was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame in 1982.

And, as he pursued the education path, Rosser also stayed attuned to the prevailing attitudes of the time. Whenever he felt that his career needed a jolt from an added credential or degree, he aimed for it and achieved it—sometimes quietly. His most clandestine days involved trips to Tuscaloosa, where, ultimately, he earned a doctorate degree from the University of Alabama.

“I still have to give A&M the credit for taking me when I had nothing and giving me a chance,” Rosser said, noting again a past that entailed coming from a broken home with family loosely anchored in the South and the North. He said A&M was like family, and it gave him a foundation and the freedom that allowed his love of music and jazz to flourish.

###